A death is a death is a death, right? We all end up needing care, comfort, a place to die, a place to go after we die, and some way to deal with the mourning and grief.

But, like anything else in life, there are so many colours in the crayon box of the death experience. It’s safer when we plan for contingencies.

Death is not something we can book in

Ask a bunch of people how they’d like to die, and most people answer they would love to be old and grey, under the doona, having a nap when death comes a-calling.

Many of us don’t get such a peaceful end.

Not all families are created equal

The Australian aged care and end-of-life systems are rather reliant on the support of families to support ageing and end-of-life experiences. However, some families may struggle to understand and cope with complex concepts like life-limiting diagnoses, palliative care, end-of-life, death, or grief. Having a contingency plan enables the identification of potential areas of support and strategies to close any gaps.

The more we can support families through the process of death, the more we can enhance their social, psychological, emotional, intellectual, and financial wellbeing, ultimately leading to a better death experience.

Maybe family isn’t the correct resource

Sometimes, the family we create from friends and community becomes the one that loves and understands us the most. In this substitute family, we may find a level of cultural understanding and support that is lacking in our family of origin.

Perhaps it would be more fitting for others who truly know us to take the lead, as they can represent us and our true essence more accurately.

Some examples where family may not be the correct choice for end-of-life care may be:

- if you find your family objects to your lifestyle, sexuality, partner or the person you are

- where differences in spiritual belief are profound and/or unlikely to be reconciled

- where complexities exist, such as mental illness, estrangement, addiction or abuse

- if you do not feel safe, respected, welcome or loved in their company.

No matter the reason you don’t feel comfortable relying on family during an end-of-life experience, it’s okay to plan something different.

Geography can be a barrier

The journey from one side of Australia to another is long, let alone if you are living in another country. It can be a costly, lengthy and sometimes out-of-reach undertaking. And that means sometimes we cannot be with a person when they die.

Virtual support has its limitations. It cannot hold a hand, mop a brow, or give a loved one a hug as they die.

And while virtual support can often fill the gaps, many families really don’t know how to go about activating it. Plus, it is not the whole story.

Having an alternative plan can help reduce the trauma associated with worrying how people are as they die and whether they are alone.

People are complex

Perhaps you want to attend someone’s bedside, but the person in question has a history of mental illness, drug abuse or alcoholism, or can revert to abusive patterns when under stress. Building a plan that helps you receive enough breaks, self-care, respite and shared care support may be vital to providing care.

Let’s put it this way – death can bring out the best and the worst in people, especially when we know death is imminent. The mix of family and death can create a heady time machine that transports us right back to painful memories, difficult childhoods, and patterns of behaviour we might enact without even recognising we’re doing so.

Having a plan to support ourselves appropriately while dealing with complex people and the emotions and reactions they can elicit is part of providing the best-quality support.

Unexpected death doesn’t discriminate

No matter how well we plan for death, we cannot cover all bases. This is especially true of unexpected death.

If you’ve ever experienced an accidental death, lost someone to Covid-19 or an unexpected medical event, or been left in the wake of a suicide, you’ll understand the push and pull of making sense of an unplanned, premature death.

Sometimes, the hardest part of death isn’t that it has occurred. It is our desire to glue the pieces together to make sense of it.

Preparing for the event may not be possible. But coming to terms with the shock can be easier with forward planning.

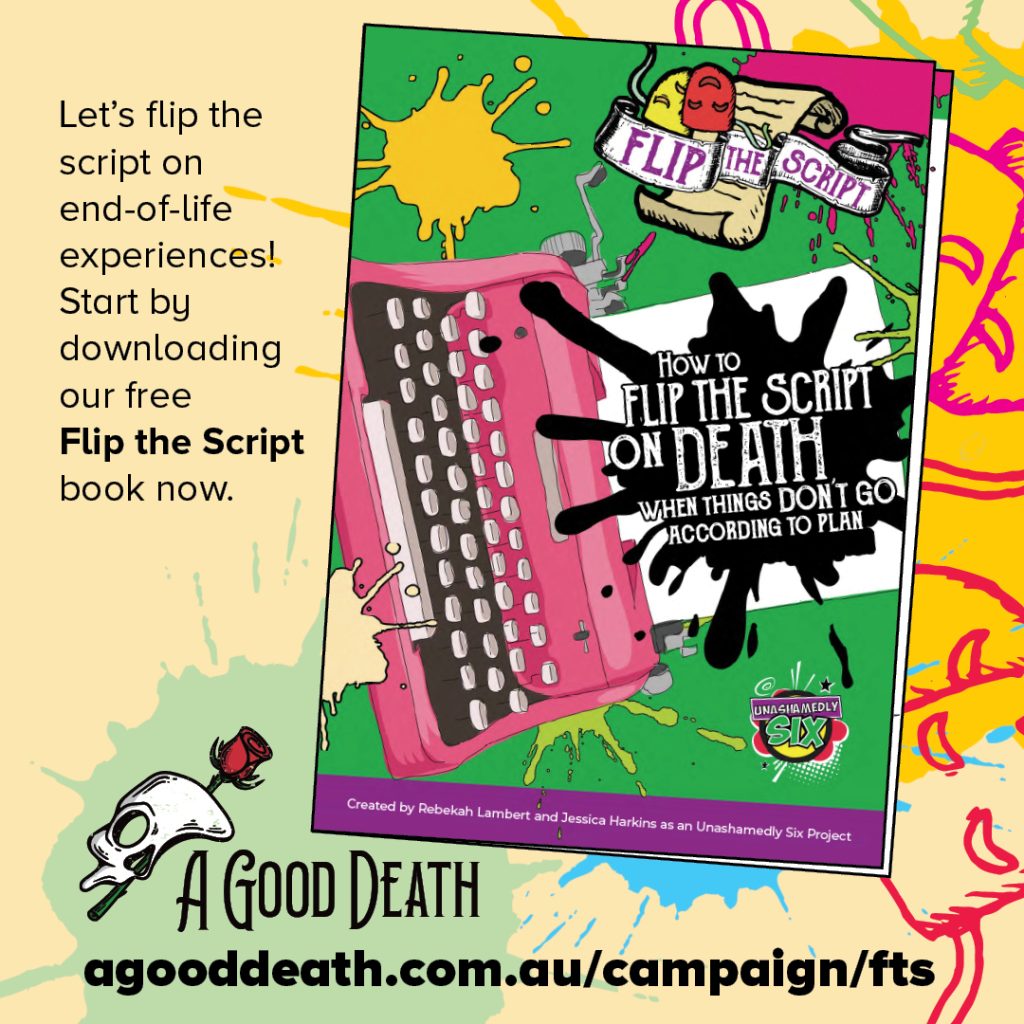

Download the Flip the Script booklet now and build yourself a contingency when things don’t go according to plan.